Susan Heller didn’t start her career pursuing change management communication, but discovered her aptitude for it almost by fate.

Heller worked at Ernst & Young (EY) for 12 years, operating first as a project manager for the firm but progressing into a communications and metrics management role later in her tenure. One of her primary responsibilities involved communicating the state of organizational affairs to the firm’s global operations group, which spanned 300 employees dispersed across three continents and several countries.

Over time, the nature of what she had to communicate shifted. She started communicating changes to employees–the “tough kind of change” like organization restructuring, changes to job roles, and even layoffs. Heller supported these efforts by opening up two-way communications channels between leadership and staff and taking ownership of the annual employee satisfaction survey, among other duties.

“Not realizing it, I started to specialize more and more in change communications,” Heller says.

Heller soon formalized that specialization with certifications in the APMG and Prosci change methodologies. Since EY, she has operated as a change manager at National Grid in Brooklyn, NY, and most recently at New York Power Authority in White Plains. Presently, she is launching Your Life Lantern, a personal coaching business.

Heller says her journey to the world of change management is not entirely unconventional. Many change practitioners first come to the profession from the worlds of project management and especially from organizational communications. The reason for this, she says, is because communication is the heart of change management.

“It’s a great transition because change is all about communicating,” Heller says. “It’s about getting to a place of mutual understanding.”

But in order for leaders to move forward from that place of understanding, they need to be adept at more than just change management communication. They need to have an intimate knowledge of how employees will process the change that lies ahead.

What employees experience in times of change

To Heller, there’s an important distinction business leaders need to understand when helping a workforce process large scale change.

“A lot of people focus on organizational change when they’re dealing with a group of people. What you need to understand is they’re a collection of individuals,” she says. “You need to understand how individual people might be feeling, why they’re reacting the way they’re reacting.”

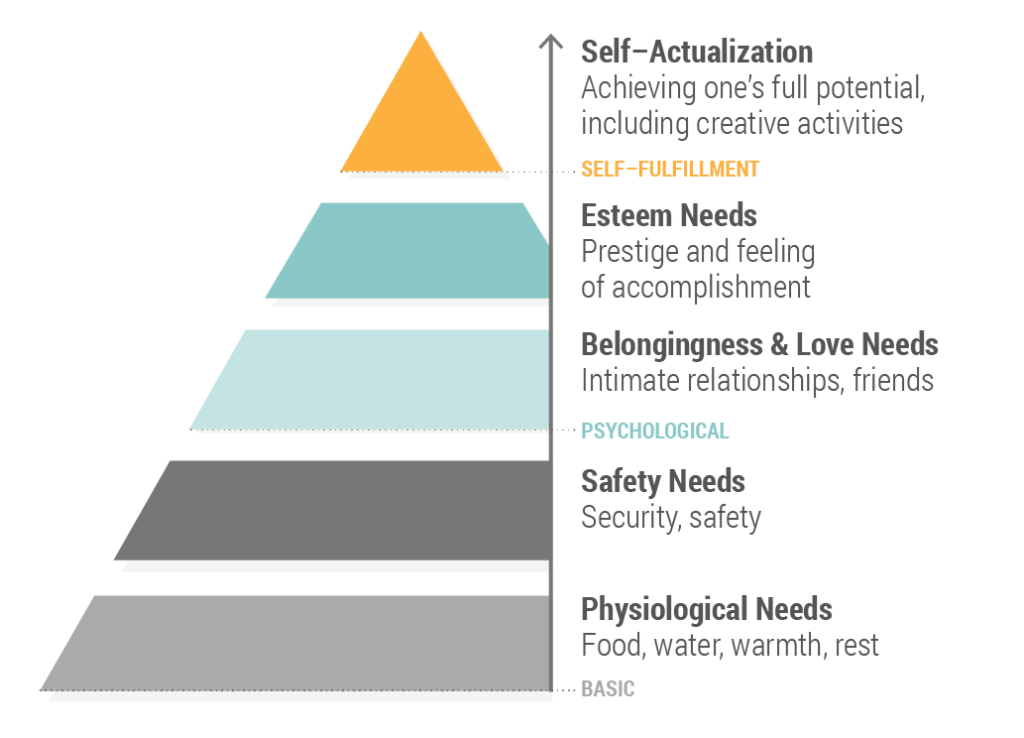

Heller points to Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs as one framework for understanding the “why.” Maslow’s theory of human motivation and psychological health diagrams human needs in a pyramid. At the bottom, our basic needs are physiological: food, shelter, water, rest. People need income to provide those things for themselves and their families. Large-scale organizational change threatens their ability to do so.

“If you start to have changes that impact those things, the response can be profound,” Heller says. “There’s a lot of fear. Fear of loss of income. Fear of not having anywhere to go. Fear of questions they’ll have to ask like, ‘If I lose my job, what am I going to do?’ or, ‘In this new role, who am I?’”

Those latter questions gesture at our psychological needs and capacity for self-fulfillment which sit further up in the hierarchy. Here, change starts to affect employees’ sense of organizational identity.

“Psychology tells us people want agency and autonomy. They want command over their destiny. They want to have some area of mastery, too. They want something that allows them to say, ‘This is what I do.’”

It is just as important that leaders acknowledge employees’ psychological needs along with the physical. When managed poorly, organizational changes that jeopardize employees’ real or perceived autonomy, agency, or mastery will eventually take a physical toll. Employees lose their ability to bring their best selves to work as the looming specter of change becomes a source of fear and anxiety.

“Studies show that organizations that go through turmoil have more sick time, accidents, more issues with customers,” says Heller. “Why? Because employees don’t feel good about their security, what they mean to the company, and their sense of belonging.”

Principles of change management communication

Organizational change is often met with resistance from employees, even when they don’t feel personally threatened by it. As Newton’s First Law of Motion states, an object in rest will stay in rest. Given the choice, most people will prefer to remain in their resting state. That is until outside forces compel them to move.

Heller says employees have a few common refrains throughout the change process. “I don’t know if I can do that.” “I don’t know if that’s for me.” “I can’t believe they’re doing this to me.” Although these might not be the things leaders want to hear from employees, they are the things they need to hear. Working through these points of resistance is a unique element of change management communication.

“This isn’t about marketing and it’s not about informing,” Heller says. “This is about constantly answering peoples’ questions, perpetually having a pulse on the organization and how they’re feeling, and being able to pivot in response to their feedback.”

Heller emphasizes that change management communication is “not about being a spin doctor” for the organization either. Communication must instead ground employees and give them an understanding of what’s to come.

“If there’s going to be job losses and changes, you have to be honest with people so they can prepare for it,” Heller says.

Honest communication allows employees to work through change emotionally and determine the path they want to take, she adds. That may mean staying with the company and working through the change, or it may mean leaving for other opportunities. But that honesty is what ultimately preserves the sense of autonomy and control employees need. Along the way, it helps leaders build a sense of authenticity and trust with employees too.

Heller says the alternative–the “spin doctor” approach or not communicating at all–will undermine the change management strategy in the long run.

“I try to tell leaders all the time, if you’re not communicating, nature abhors a vacuum,” Heller says. “People will fill it. They’ll fill it with rumor and conjecture. That’s worse than no information.”

Related: How to Pull Off Organizational Culture Change

Accounting for change fatigue

Agile workflow models are quickly becoming the new norm in the business world, and they tend to work well with change management. Agile’s shorter cycles of development, punctuated by periods of reflection and reassessment, allow leaders to strategically and flexibly approach change. But to Heller, these models provide a less obvious benefit: an antidote for change fatigue.

“You can’t do this marathon style. Human beings need more care than that,” she says. “You can’t go years on one change and never see the light of day. You’ve got to break it up into smaller changes.”

There’s a reason why so many business leaders today are saying change is now a constant. Organizational change can be a protracted affair, sometimes spanning several years depending on the size of the company. But that doesn’t mean employees have to process it all at once.

Heller says it’s necessary for employees to be able to reflect on their change experiences, not just with the leaders of the company but with each other. To that end, leaders should provide spaces for employees to share their feelings, openly voice feedback without fear of repercussion, and even make room to celebrate successes along the long change journeys.

“Because you’re dealing with a collective of feelings, thoughts, and opinions, it’s good to surface them,” she says. “You make people realize, this isn’t the change manager telling you how to feel. This isn’t leadership telling you, either. This is what you as a collective are thinking and feeling.”

These are moments laden with unique potential in change management communication. Through open discussion with peers and leaders, employees find opportunities to reclaim their lost sense of agency–or reaffirm it if it chose to stay.

For Heller, making space for these moments could mean finding the one big success story the company “needs” to hear. “Getting the people who are highly resistant engaged in creating the change is a great technique because it gives them back that lost sense of control,” she says. “It lets them know they genuinely have a voice.”

But when change becomes overwhelming for employees (and leaders too), these moments of reflection are essential for discovering much-needed pivot points. Adhering too rigidly to an initial change strategy can be potentially hazardous. When leaders become too entrenched in a change methodology that simply isn’t working as well as it could, it wears employees out.

“When there’s failure and things are not working right in an initiative, you have to be flexible,” Heller says. “You have to be able to do self-assessment.”

But regardless of whether you’re celebrating successes or working through points of resistance, Heller’s experience has made one lesson incredibly clear. During organizational change, leaders must leverage change management communication to connect with employees as the people they are:

“It’s about listening with empathy and communicating with empathy.”

6 min

6 min